From March 2016 to May 2020, I worked with

Professor David Grier in NYU Physics' CSMR department.

My research focused on not only building of an acoustic imaging device, but also discovering the uses and

nuances of Acoustic Holography.

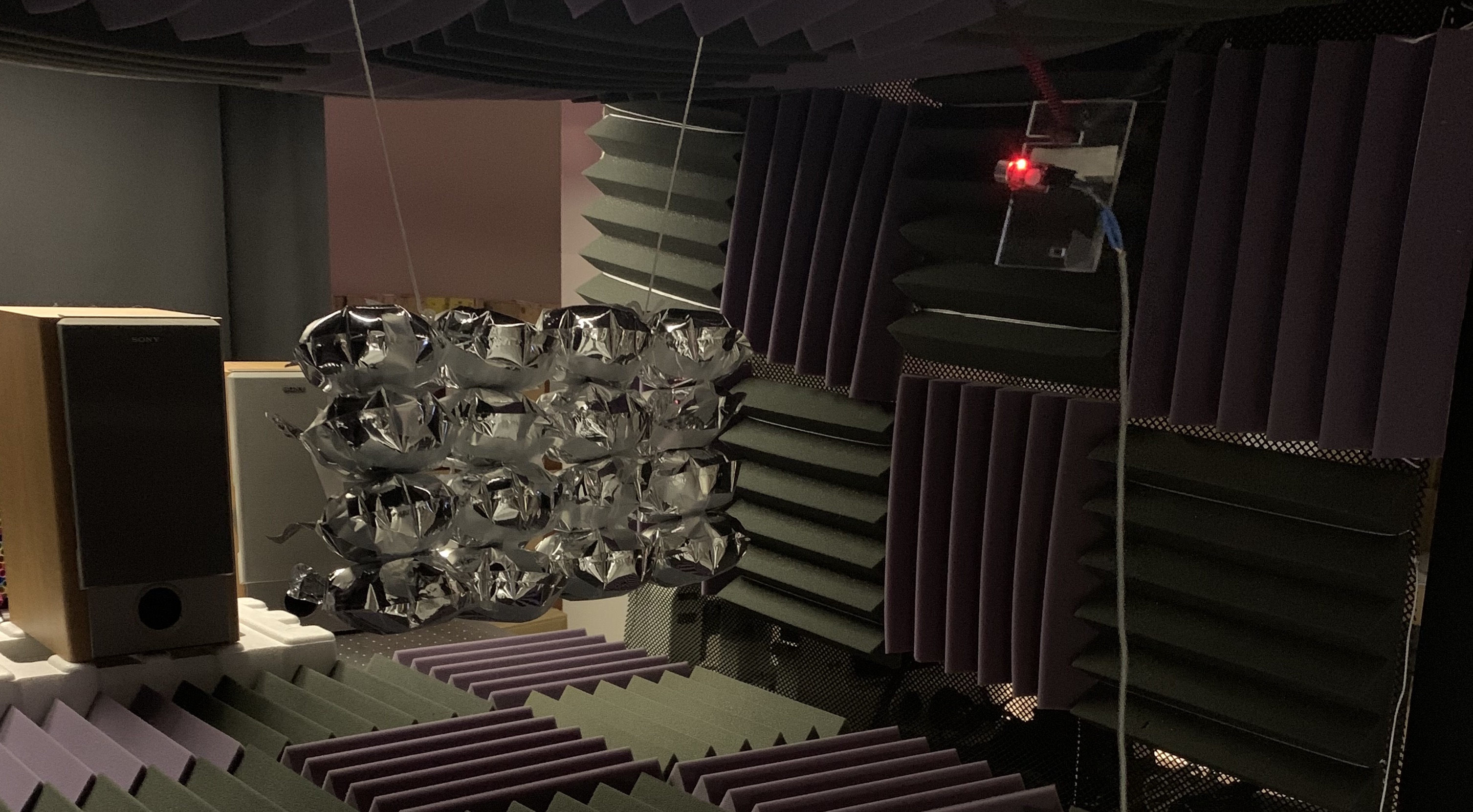

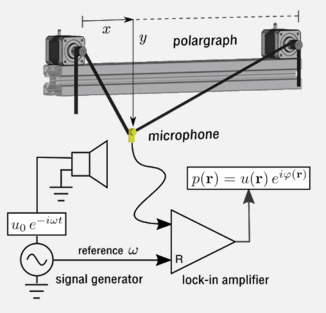

In the large-scale device that we built, we have a microphone moving in a serpentine pattern (in x and y) while

attached to stepper-motors controlled by an Arduino.

The microphone is listening to a speaker that blasts a specific frequency (often 10-16 kHz, a range many in the

lab called "annoying").

This speaker is told the specific frequency by a signal generator, which then tells the lock-in amplifier what

to look for.

The lock-in amplifier simultaneously takes in data from the microphone in order to emit a wave function,

p(

r), in terms of amplitude, u(

r), and phase, phi(

r).

This has a lot of advantages over both optical and other acoustic holographic methods as ours is able to scan a

large range, over the course of various frequencies, and return both an amplitude and phase.

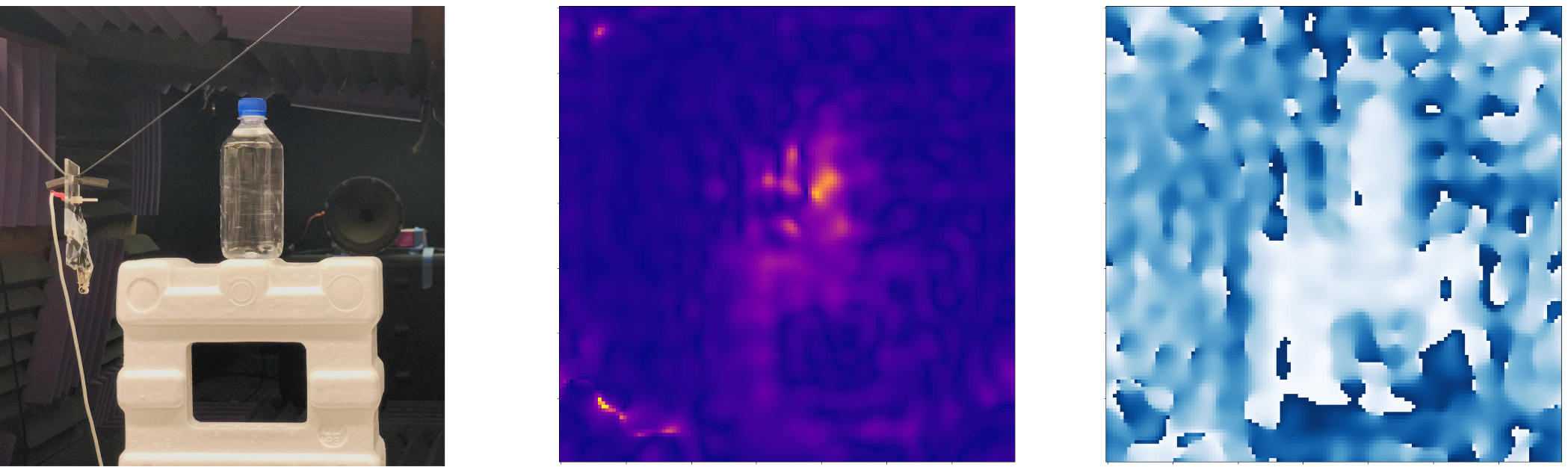

After we built our machine, we decided to test it with a water bottle between the speaker and microphone.

And we're able to see the water bottle, its square shape, and even its cap. (shown to the right)

When we try to control for the noise of the room by dividing out a scan of just the background,

we see a resonance in the water bottle: a concentration of energy.

This concentration of energy can perhaps be best illustrated as an opera singer, hitting a note that makes a glass

break.

Where the crack starts is a weak point, and when the energy builds up it causes the crack to expand and the glass

to shatter.

And became especially interesting during my Central Park internship,

bringing up the brief exploration into how acoustic holography,

specifically our camera, can be used for sculpture conservation.

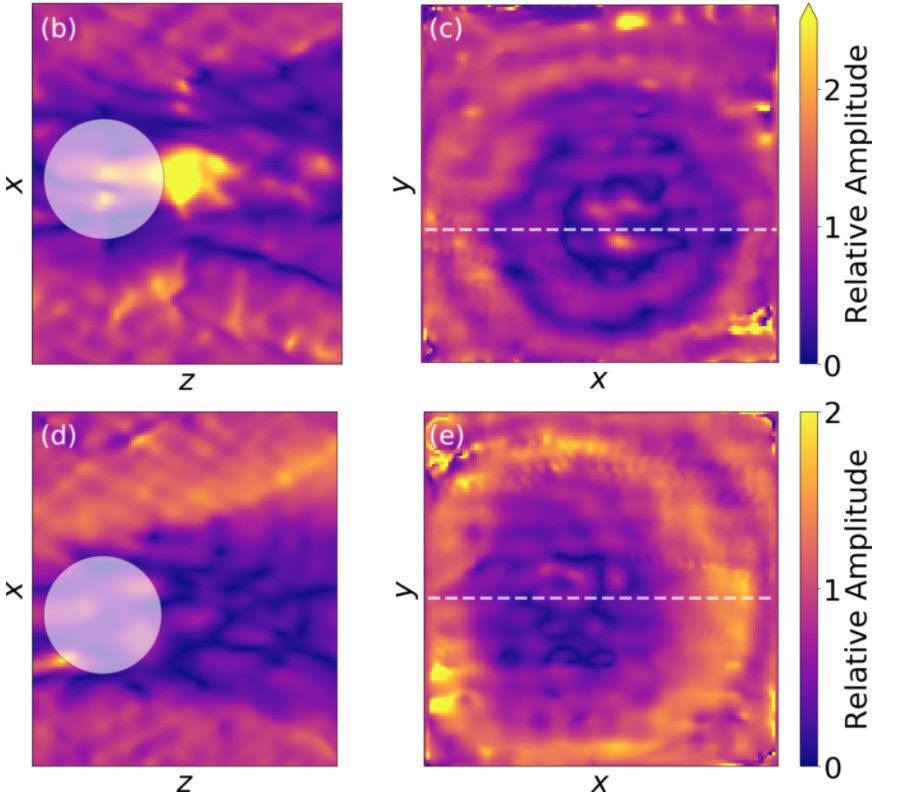

In addition to the water bottle, we also scanned two different balloons: one filled with Helium (He) and one

filled with Sulfur-Hexafluoride (SF6).

Where the speed of sound is around 1,000 m/s and 135 m/s, respectively. For reference, the speed of sound in air

is 343 m/s.

And, what we were able to see is that these balloons act as a converging and diverging lens!

The SF6 balloon acts as a converging lens, concentrating the sound "energy", while the He balloon diverges the

sound "energy".

This is seen in the plot above. SF6 at the top and He at the bottom, and the lighter grey shade is meant to show

the placement of the balloon in these slices.

These results are published in our paper:

"Flexible wide-field high-resolution scanning camera for continuous-wave acoustic holography"

(click here)

WHAT'S NEXT (for acoustic holography)?

frequency chirp:

We re-configured the SR830 lock-in amplifier as well as our GUI design in order to produce a "chirp" from the

speaker (ranging from 600 - 13000 Hz).

At each frequency, we were able to take data and obtain the position, amplitude, and frequency. Curious?

Check out my github here .

phononic crystal:

We then planned to use the frequency chirp/sweep, as well as the other elements detailed earlier to make the

acoustic equivalent to a photonic crystal (a phononic crystal).

This was a lattice of small, sphere-esque balloons filled with alternating Helium and SF6, and is shown below: